Abstract

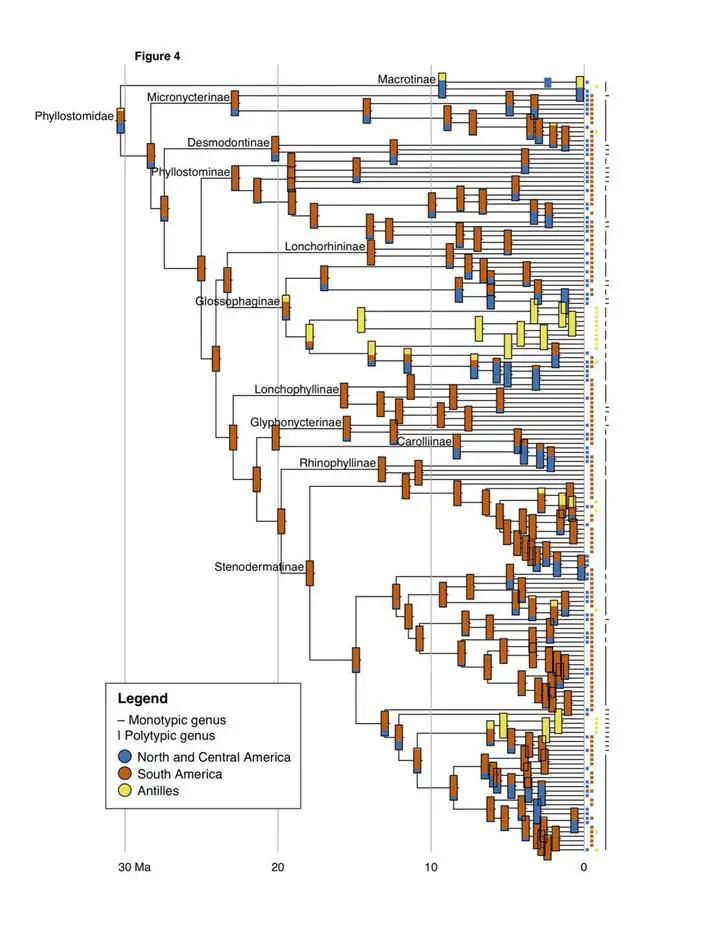

Traditionally, the phylogeny of phyllostomids contained a few subfamilies sharing similar cranial and ecological traits. Family-wide genetic sequence data starting in the early 2000s, however, showed that this phylogeny obscured the taxonomy, biogeography, and evolution of ecological traits in the family. Current phylogenies strongly support the monophyly of 11 subfamilies, as well as most relationships among them. Nonetheless, the positions of several key groups are not well-supported and require further analyses, including: 1) Micronycterinae relative to Desmodontinae, 2) Lonchorhininae, and 3) the genus-level resolution of Miocene fossils. Historical biogeographic analyses have revealed a South American origin for most subfamilies; have inferred widespread and multi-continental distributions for ancient ancestors; and have rejected a special influence of Quaternary glaciations on recent speciation. These analyses have also confirmed North and Central America, as well as South America, as independent centers of diversification for some subfamilies (e.g., Macrotinae), as well as within subfamilies (e.g., Glossophaginae). These parallel centers of diversity might result from the absence of continuous dry habitat corridors between the continents, but this hypothesis has not been tested using phyloclimatic methods. Biogeographic analyses of individual genera have demonstrated the importance of the Andes for diversification in Platyrrhinus, Sturnira, and Uroderma, as well as the critical role of humid forest corridors between Central and South America for the long-term dispersal of these lineages.