Cali lives up to CoP16, CBD fails to deliver money deal

Dávalos at the entrance of the CoP16 Blue Zone.

Dávalos at the entrance of the CoP16 Blue Zone.

Will biodiversity make it? Out and about at the 16th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), read the write-up at the Institute for Globalization Studies news. Or below the fold.

Last week, I returned from the 16th Conference of the Parties (or CoP) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in Cali, Colombia. This takes a bit of unpacking. Back in 1992, the United Nations sponsored the first CBD as a mechanism to halt the current extinction wave, the one our juggernaut of a human economy is causing, even as I write. Since then, pretty much every country in the world has signed and ratified the CBD, though the United States signed then did not ratify it. In any case, the CBD has kept chugging along meeting every two years to reach consensus on agreements then actions to halt and even reverse the extinction wave. As a scientist working on biodiversity in tropical countries, in 2022, I had the privilege of working with a large team to provide expert input so that the agreed-upon targets had a chance of curbing global extinctions. Because our team represented no single country, or party, to the Convention, this is analogous to the way expert testimony could be used in Congress here in the US. Ambitious targets were set to conserve life (animals! Plants! Fungi! Entire ecosystems!) on land and sea and the Global Biodiversity Framework was thus adopted in a very windy and frozen Montreal two years ago.

That set in motion the chain of events that took me to the decidedly less Arctic Cali, Colombia, in a totally unexpected manner. Back in Montreal, the parties decided to make good on their ambitious goals and implement (read: fund) them the next time, in Turkey. But 2023 earthquakes prevented Turkey from following, and for almost half of 2023, neither the parties nor the scientists and activists knew where CoP16 would be. Enter Colombia, a megadiverse country hosting multiple distinct biodiversity hotspots, a state-backed national goal of becoming a biodiversity superpower, and in possession of Susana Muhamad, a minister of the environment with a long track record of environmental activism. Cali was selected at the international equivalent of the last minute, just last February and so had much less time to prepare than customary. Could scrappy Colombia and its Caleños (people from Cali) pull off such an undertaking?

Reader, they did it! Even at airports, banners and exhibits proclaimed the importance of biodiversity everywhere. For CoP16, Cali itself was transformed. Streets, manhole covers, vents, everything highlighted biodiversity, until the Convention became inescapable. This may seem ineffectual, but I suspect it has brought biodiversity to the streets as never before. Take the multicolored tanager, Chlorochryssa nitidissima, a bird that lives only on the Pacific versant of the Western Cordillera of Colombia, by most accounts the wettest rainforests in the world. As an undergraduate student, I went to the remote Munchique National Park and saw it as clouds rising from the Pacific Ocean briefly cleared. This memory is an inspiration to continue working to prevent the destruction of its forest home, no matter the odds. Yet, my deeply felt sense of the sublime will do nothing to stave off its demise, only action by people on the ground will and we can only save what we know. Over two short weeks, this one sign above a car park on Cali’s 4th Avenue reached more eyes and minds than my decades of presentations and publications!

But banners and slogans don’t generate change, people do, and this CoP was a record for public participation. The Green Zone, the area of the CoP open to the public, was like a block party along the Cali River, but for biodiversity. Expected to attract about 150,000 visitors during the 12 days of the Convention, as many arrived in just three days. All of Cali was packed, with hotel occupancy at record rates and delegates packed both in Cali and towns surrounding it. Logistics were impeccable. Buses from the city’s service, were repurposed to connect the Green Zone with the secure area, or Blue Zone. One of the lines was all electric, and this new system outlives the Convention already, jumpstarting the transition to clean energy for local transport.

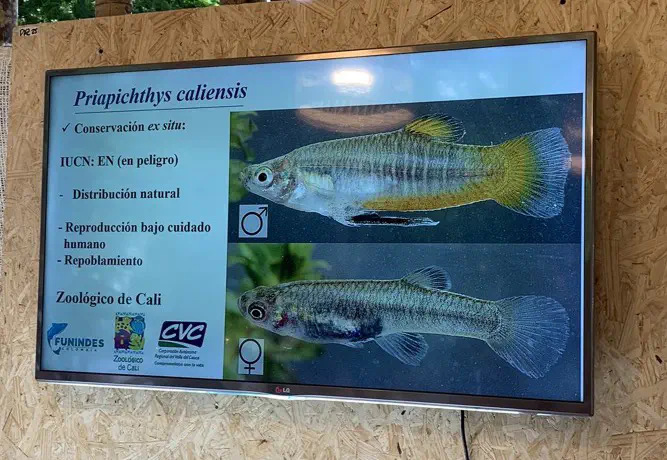

But not all was fun and dance in the CoP Green Zone; stands reminded everyone nature is at stake! For example, an environmental assessment of the freshwater fish Priapichthys caliensis found individuals only along 25-m of one of the Cali River’s tributaries. This is only known thanks to a small local NGO called Funindes, which has a backlog of many other species to monitor. There were sobering exhibits. For example, the cemetery of recently extinct species showed species lost to the world as recently as the 2000s, in places as disparate as the Hawaiian archipelago, Tasmania, Costa Rica, or the Galapagos. But not all is lost, the garden of second chances features the many species that have been rescued from the brink of extinction by conservation action, including the iconic American bald eagle, or the Iberian lynx.

My own participation featured the rescue of just one such species, the Jamaican flower bat, Phyllonycteris aphylla. Back in the 2000s, I joined expert panels determining the extinction threat status of many species of bats in Latin America and the Caribbean. As a publication featured dozens of locations for the Jamaican flower bat, I classified the species as not endangered at all. But I had overlooked the dates of those sightings, all were old, some as old as 30 or 50 years. An expert based out of Jamaica, Dr. Susan Koenig, pointed this out, adding that Andrea Donaldson from the National Environmental Planning Agency of Jamaica had found this species at just one cave in the whole country. Susan and I then worked together to recategorize this species, finding it was critically endangered. This enabled a NGO, Bat Conservation International, to kick into gear and raise funds to save the species from extinction. Their prompt action and support from the Jamaican landowner who wanted to leave a legacy for future generations have made all the difference. Their BCI-Jamaica team now work together on excluding feral cats that threaten bat pups as well as restoring the habitat where these bats forage.

Global events like the CoP can seem far removed from immediate threats to biodiversity, such as ecosystem loss and climate change. In the end, this round of negotiations succeeded in establishing the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (or TFFF) by paying out dividends to conserve the world’s most biodiverse forests. It also established the Cali Fund, to draw from large companies that make use of genetic resources in support of biodiversity. Most consequentially, Indigenous peoples now have their own seat at the negotiation table, a landmark decision. But there was no agreement on a mechanism to finance the annual $200 billion needed to avert extinctions, and the CoP ended as delegates vacated the room to take their flights. It was not the expected outcome, but watching so many come together for biodiversity, especially in the Green Zone, was invigorating. Let’s hope all this activism translates into action!